Published on Dec. 20, 2024

The Importance of Colostrum in Swine Production

In this article, discover how effective colostrum management can enhance piglet health, survival, and overall swine productivity.

Colostrum is the first milk a sow produces shortly after, even during, the farrowing process. Its production is triggered by a cascade of hormones before farrowing begins1. During this initial colostral phase, the sow continuously allows her piglets to access her udder, enabling them to move from teat to teat and consume colostrum2,3.

Colostrum is vital for the survival and growth of piglets in their earliest stages of life, as it provides essential nutrients, energy, and antibodies. Its significance is particularly important in modern swine production, where optimizing piglet health directly influences productivity and profitability. The "three Qs" of colostrum management, as highlighted by the Hypor technical team, emphasize the key factors:

- Quality – The percentage or yield of fat and immunoglobins

- Quantity – Sufficient intake for each piglet

- Quickness – Piglets need access to this rich resource as quickly as possible.

Effective management of colostrum is crucial for the health and performance of piglets, contributing significantly to the overall success of farm operations.

Colostrum: An Overview

Piglets are born without a fully developed immune system. Unlike humans, pigs do not transfer antibodies from the mother to the fetus through the placenta. This means piglets rely entirely on colostrum for passive immunity.

Recent research involved collecting colostrum from sows during the first 24 hours after farrowing and analyzing its contents4. The amounts were averaged over the period of collection. Milk was also collected and analyzed later in the lactation period. The findings are summarized in Table 14.

Colostrum contains a compound called Immunoglobulin G (IgG), which is essential for providing piglets with passive immunity while they are nursing5. As indicated in Table 14, colostrum is significantly richer in proteins, fats, and carbohydrates compared to regular milk. These nutrients are crucial for piglets, as they are born with very low energy reserves and minimal body fat.

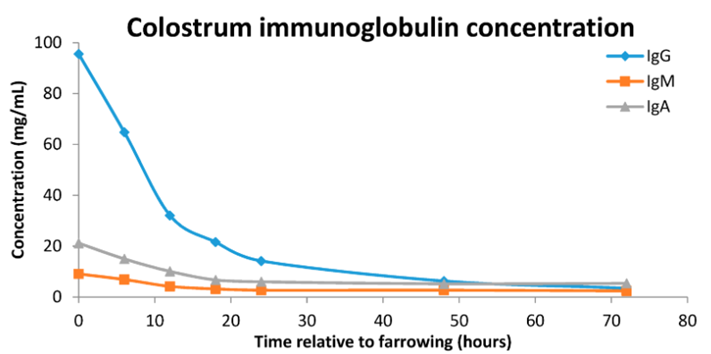

Colostrum is secreted in the greatest amounts within the first 12 hours post-farrowing, and its production significantly decreases between 12 to 24 hours (Figure 1) and it typically depletes around 40 hours after the first piglet is born6. Moreover, the limited window for the production of these immune components coincides with the piglets' ability to absorb and utilize them.

In large farm animals like pigs, the intestine can close the wider channels necessary to absorb large IgG molecules as soon as 24 hours after birth, effectively halting their ability to take in these important immunological factors7. Additionally, piglets should not be cross-fostered before validating colostrum intake, as they cannot absorb and utilize other immunological components, such as lymphocytes, from foster sows8. This highlights the importance of timely and sufficient colostrum consumption from their mother within the first few hours of life.

| Item | Colostrum | Milk |

|---|---|---|

| Fat, % | 6.21 | 6.53 |

| Lactose, % | 3.78 | 5.37 |

| Protein, % | 10.7 | 4.98 |

| Dry Matter, % | 22.6 | 17.5 |

| IgG, mg/mL | 40.7 | NA |

Colostrum not only provides essential components for the development of a piglet’s passive immunity, but it also serves as a potent energy source. Colostrum is packed with high-quality proteins and energy sources essential for piglet survival by supporting their metabolic needs during the critical first hours of life.

Newborn piglets have limited energy reserves and low body fat, making the nutrient-dense composition of colostrum critical for meeting their metabolic needs for thermoregulation and overall survival. Lightweight piglets, which we consider to be less than 1.0 kg, are more likely to present signs of hypoxia at birth, have reduced colostrum intake in the first 24 hours9. This is mainly attributed to their size or weakness at birth, as they are more likely to miss more nursing events or are in greater competition for an available and functional teat.

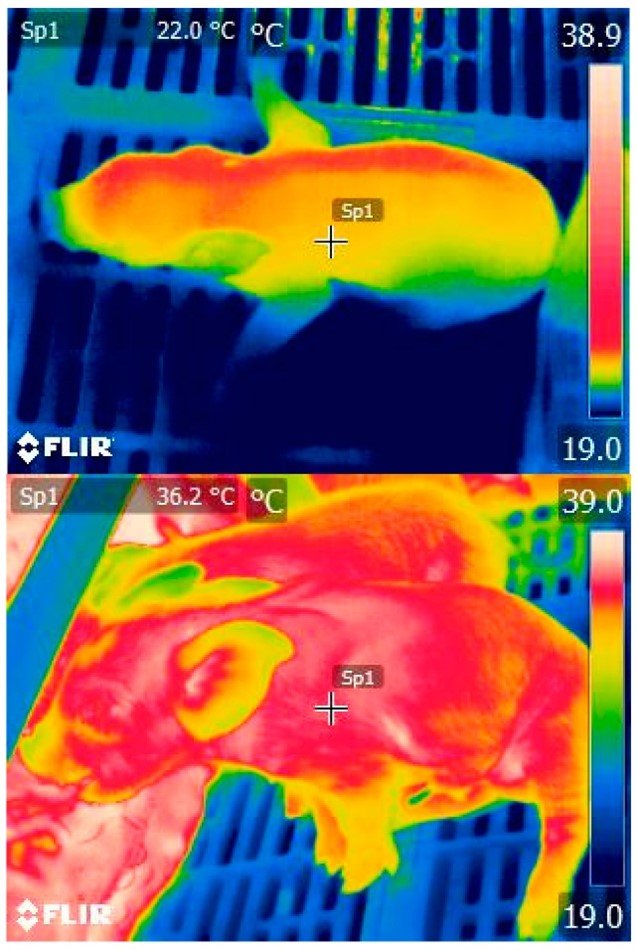

Additionally, hypothermic piglets and those with low viability—indicated by a rectal temperature below 38°C—are less likely to consume sufficient colostrum, further increasing their vulnerability10. Thermal imaging studies have shown that piglets who receive colostrum achieve higher body temperatures, which enhances their viability (Figure 2)10.

Colostrum also has growth factors that aid in the development of the digestive tract11. These growth factors and bioactive peptides in colostrum promote intestinal growth, which enhances nutrient absorption efficiency. This early development lays the foundation for improved feed conversion and growth rates during the nursery and finishing phases. Production efficiency can be influenced within the first 24 hours of life, making it essential for piglets to individually consume enough colostrum.

The ideal amount of colostrum needed per piglet is 250 grams12. This intake should be achieved over several nursing sessions12. This colostrum intake should occur within the first 12 hours after birth, or as soon as reasonably possible, because of the “closure” of the intestinal wall which was previously mentioned.

Colostrum and the Impact on the Pig

Colostrum intake has a significant impact on piglet health and performance. Timely and adequate intake of colostrum significantly reduces pre-weaning mortality. Piglets that do not receive enough colostrum are more susceptible to infections, starvation, and weakness, which can lead to higher losses for producers. Colostrum intake is heavily determined by the piglet’s ability to reach the teat.

Research has shown that piglets ingesting less than 200 grams of colostrum at birth have a pre-weaning mortality rate of 43.4%, while those that consume more than this amount have a mortality rate of only 7.1%13 Moreover, piglets that die during lactation typically exhibit lower weight gain, weight loss, lower rectal temperatures, increased cortisol levels, and decreased plasma IgG and glucose levels13.

Another study found that for every 100 grams increase in piglet birth weight, their individual colostrum intake increased by 28 grams2. Lighter birthweight piglets require additional management in split-suckling, possible teat training, or cross-fostering to give them an advantage with piglets relative to their own size. While some events during farrowing are beyond the herdsman's control, many issues can be mitigated through proper colostrum consumption and exceptional care of piglets on their first day.

Adequate consumption of colostrum has been shown to significantly enhance the potential for offspring to become full-value finishers, as the benefits of colostrum extend well beyond the farrowing period. Colostrum contains various growth factors, such as Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) and Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), which are crucial for the development and maturation of the piglets' gastrointestinal tract and other organs14. These bioactive components support the overall growth and development of piglets, setting a strong foundation for their future health and productivity.

Both colostrum intake and the birth weight of piglets significantly affect their weights at weaning, during the growing phase, and at finishing15. One study found piglets who consumed less than 290 grams of colostrum weighed approximately two kilograms less at 42 days, compared to piglets of the same age who consumed more than 290 grams13. Additionally, higher colostrum intake was shown to benefit piglets with lower birth weights more significantly than their littermates, leading to reduced pre-weaning and nursery mortality15.

Colostrum can also impact the female reproductive system influencing the later development of the reproductive tract. For instance, the hormone relaxin found in colostrum is crucial for the development of the uterus in pre-pubertal gilts, pregnant sows, and their daughters within a few weeks after birth16.

Research indicates that piglets raised on milk replacers without supplemental colostrum exhibit lower gene expression related to the growth of the endometrium, or the membrane that lines the uterus, and delayed gland development within the tissue17. Additionally, another study found that low colostrum intake is associated with a later onset of puberty and a reduced number of piglets born to the sow18.

Effective Strategies for Colostrum Management

Validating adequate colostrum intake for all piglets is essential, yet it can be challenging. To address these challenges and improve piglet survival rates, effective colostrum management practices are necessary. One key practice is ensuring that piglets have early and frequent access to the sow. This can be achieved by encouraging frequent nursing, keeping the piglets close to the udder, and minimizing disturbances.

It’s important to realize that not all piglets in a litter have equal access to the sow’s teats. Smaller, weaker, or last-born piglets may require assistance to access colostrum. Split suckling can help in these cases, especially when there are more piglets than functional teats. This should be performed as soon as possible after farrowing, ideally within the first 12 hours. We recommend organizing the piglets into two groups:

1. Small and last-born piglets

2. Larger and first-born piglets

Conduct five rotations of 30 to 45 minutes each, starting with group 1 (small and last-born piglets) at the udder. It is critical to keep the piglets that are not nursing separated, dry, and warm. Additionally, it’s important to consider that early cross-fostering (within 12 hours post-farrowing) may disrupt a piglet’s colostrum intake from its own mother, potentially compromising its health and performance later on.

Conclusions

Colostrum is essential for the care of neonatal piglets, as it provides the immunity, nutrition, and energy they need for a strong start in life. Swine producers who prioritize colostrum intake through effective management practices can enhance piglet survival and growth, which ultimately improves the overall productivity and profitability of their herds.

Key management strategies include ensuring proper feeding, ensuring vaccinations are up-to-date, and managing stress levels. These practices are crucial for optimizing both the quantity and quality of colostrum from the sow. Investing in colostrum management during lactation is critical for sustainable and efficient swine production.

In general, piglets that receive adequate colostrum experience improved growth rates and reduced susceptibility to diseases. Furthermore, those that are future breeding females are more likely to develop better reproductive health, contributing to a healthy and productive herd.

References

- Farmer, C., & Quesnel, H. (2009). Nutritional, hormonal, and environmental effects on colostrum in sows. Journal of Animal Science, 87(suppl_13), 56–64.

- Devillers, N., Farmer, C., Le Dividich, J., & Prunier, A. (2007). Variability of colostrum yield and colostrum intake in pigs. Animal: An International Journal of Animal Bioscience, 1(8), 1033–1041.

- Quesnel, H., Farmer, C., & Foisnet, A. (2011). Relations between sow hormonal concentrations around parturition and colostrum yield. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Farm Animal Endocrinology (ICFAE 2011) (p. 69). Bern, Switzerland, August 24–26, 2011.

- Vodolazska, D., Feyera, T., & Lauridsen, C. (2023). The impact of birth weight, birth order, birth asphyxia, and colostrum intake per se on growth and immunity of the suckling piglets. Scientific Reports, 13, 8057.

- Quesnel, H. (2011). Colostrum production by sows: Variability of colostrum yield and immunoglobulin G concentrations. Animal, 5(10), 1546–1553.

- Klobasa, F., Werhahn, E., & Butler, J. E. (1981). Regulation of humoral immunity in the piglet by immunoglobulins of maternal origin. Research in Veterinary Science, 31(2), 195–206. PMID: 7323466

- Rooke, J., & Bland, I. M. (2002). The acquisition of passive immunity in the newborn piglet. Livestock Production Science, 78(1), 13–23.

- Bandrick, M., Pieters, M., Pijoan, C., Baidoo, S. K., & Molitor, T. W. (2011). Effect of cross-fostering on transfer of maternal immunity to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to piglets. Veterinary Record, 168(4), 100.

- Deen, M. G. H., & Bilkei, G. (2004). Cross-fostering of low-birthweight piglets. Livestock Production Science, 90(2–3), 279–284.

- Alexopoulos, J. G., Lines, D. S., Hallett, S., & Plush, K. J. (2018). A review of success factors for piglet fostering lactation. Animals, 8(3), 38.

- Thymann, T., Burrin, D. G., Tappenden, K. A., Bjornvad, C. R., Jensen, S. K., & Sangild, P. T. (2006). Formula-feeding reduces lactose digestive capacity in neonatal pigs. British Journal of Nutrition, 95(6), 1075–1081.

- Quesnel, H., Farmer, C., & Devillers, N. (2012). Colostrum intake: Influence on piglet performance and factors of variation. Livestock Science, 146(2–3), 105–114.

- Devillers, N., Le Dividich, J., & Prunier, A. (2011). Influence of colostrum intake on piglet survival and immunity. Animal, 5(10), 1605–1612.

- The Pig Site. (2021). Essential role of colostrum for piglet performance. Retrieved December 17, 2024, from https://www.thepigsite.com/articles/essential-role-of-colostrum-for-piglet-performance

- Declerck, I., Dewulf, J., Sarrazin, S., & Maes, D. (2016). Long-term effects of colostrum intake on piglet mortality and performance. Journal of Animal Science, 94(4), 1633–1643.

- Bagnell, C. A., Yan, W., Wiley, A. A., & Bartol, F. F. (2005). Effects of relaxin on neonatal porcine uterine growth and development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1041(1), 248–255.

- Bartol, F. F., Wiley, A. A., Miller, D. J., Silva, A. J., Roberts, K. E., Davolt, M. L., Chen, J. C., Frankshun, A. L., Camp, M. E., Rahman, K. M., Vallet, J. L., & Bagnell, C. A. (2013). Lactation biology symposium: Lactocrine signaling and developmental programming. Journal of Animal Science, 91(2), 696–705.

- Vallet, J. L., Miles, J., Rempel, L. A., Nonneman, D., & Lents, C. (2015). Relationships between day-one piglet serum immunoglobulin immunocrit and subsequent growth, puberty attainment, litter size, and lactation performance. Journal of Animal Science, 93(6), 2722–2729.