Published on Sept. 9, 2024

Lighting Requirements: Why is it Important to Maintain Proper Lighting in the Barn?

Lighting is one often overlooked area of importance on the farm. It is important to have a proper light plan (intensity and photoperiod) for the needs of each production phase. While electricity use for lighting is a small portion of your cost of production, selecting efficient lighting systems can improve your bottom line.

In the day-to-day work there is to do on a farm, some non-essential maintenance may be easily overlooked until it becomes a necessity. However, it is important to remember that general upkeep, maintenance, and cleaning can make a difference in the barn environment. Light may be one element that can be missed, but adequate lighting is important when realizing its effects on the animal. Perceived light influences the biorhythm of pigs, their social behaviors, activities, and their productive and reproductive results.

Science highlights the effect of appropriate lighting on sow reproductive performance. These effects can be described as an improvement in returns in heat (such as weaning to service intervals and non-productive days), and during lactation which can positively influence piglet weaning weight. However, lighting is still unfortunately not yet well valued by some producers around the world. If lighting can increase efficiency, it represents an advantage in economics as well. Therefore, it is important to have a proper light plan (intensity and photoperiod) for the needs of each production phase. While electricity use for lighting is a small portion of your cost of production, selecting efficient lighting systems can improve your bottom line.

Light

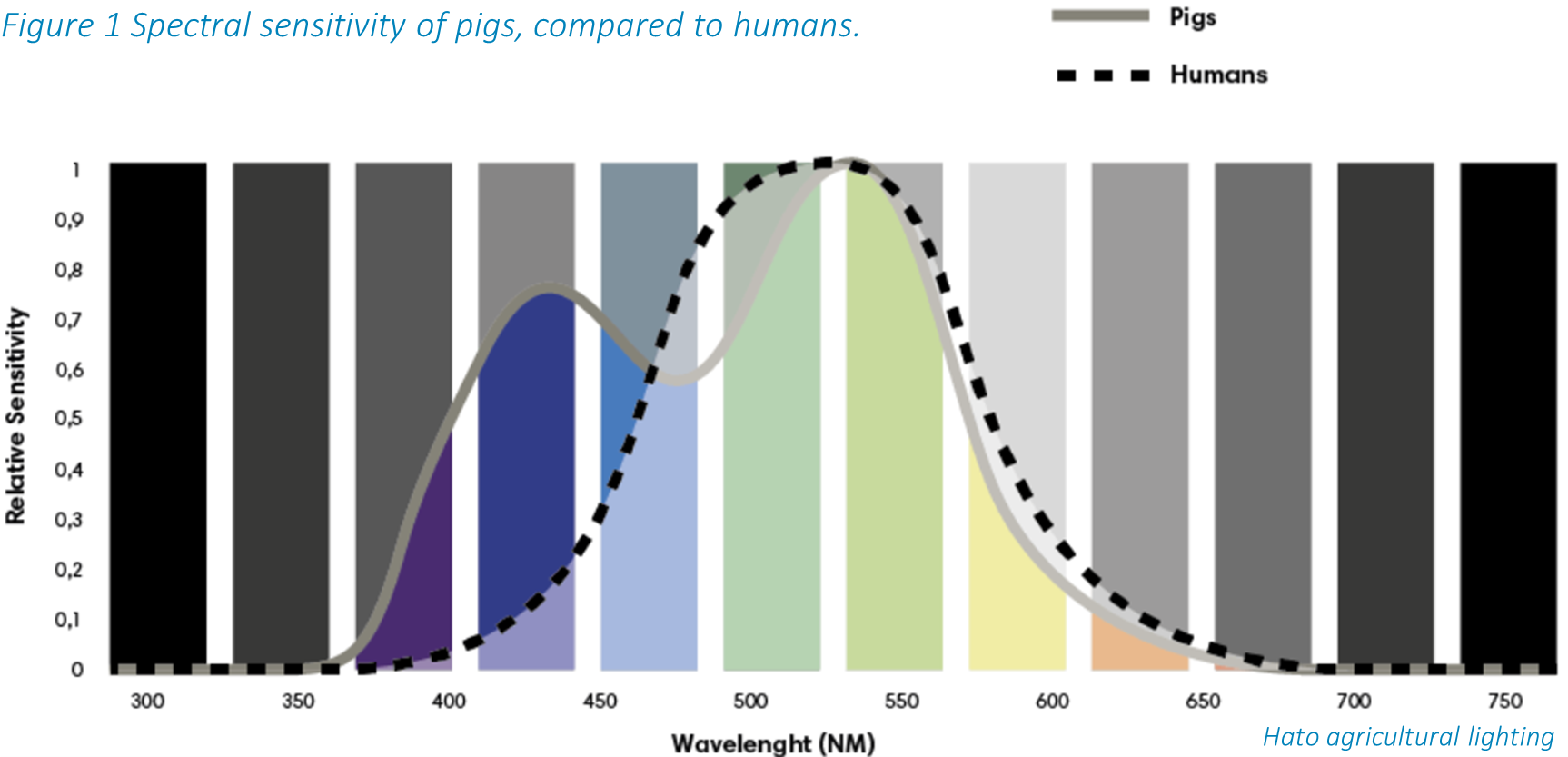

Visible light is described as the wavelengths visible to the human eye and may differ from the pig due to their ability to detect other wavelengths.1 An example of this dissimilarity is shown in Figure 1.2 Adapting lighting to the visible spectrum of pigs helps to improve their vision. This will lead to the optimization of social behaviors, better use of the environment, and a decrease in stress. Due to this effect, it is important to provide uniform light distribution to avoid overly illuminated areas and shadows which might affect pig behavior and/or performance.

It is possible to objectively measure visible light using a light meter. These instruments can measure various types of intense lighting, as some barns may be using different styles of lighting. An example of a light meter is shown in Figure 2. Lux (lx) is a measurement of the brightness of light striking a surface that has an area of one square meter, and it is used to describe lighting in most swine barns.3 The light intensity should be measured at the eye level of the animal. It is evident the appropriate light intensity and photoperiod can enhance most sow reproductive performance indicators. In literature, photoperiod appears to be more widely agreed upon than light intensity. Therefore, more research is required to better understand the ideal light intensity for each stage of the pig.

A light flicker is a rapid change in the light output of a lamp, and it can be perceived by pigs as well as humans. Considering humans, the flickering of light can influence their health and well-being and should have the same negative effect on pigs. As such, 100% flicker-free lighting should be recommended.2 T8 fluorescent (which has very little or no flicker) and LED lighting can offer energy cost savings of up to 85%, which is preferable in terms of lifetime costs and features than older incandescent lights.3

Sow Reproduction

Wild pigs will adapt their breeding season to match it most favorably to food availability, and the chance of their litter surviving and reproducing.4 This seasonality effect has been mitigated in commercial breeding facilities with artificial light programs. Despite the use of artificial lights, there still seems to be some evidence domestic pigs retained some seasonal sensitivity from their wild counterparts. This is marked by a drop in fertility during certain months of the year.5 While both temperature and photoperiod have an impact on the onset of breeding season, photoperiod is the most important factor.6

The hormone melatonin has been recognized for years as being associated with vertebrate reproductive rhythms, and seasonal cycles of metabolic activity, immune function, and behavioral expression.7 Melatonin is released from the pineal gland in response to stimulus observed through the eye when there is a change in photoperiod, or the period observed where there is daylight.6 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is a precursor to hormones important in the reproductive cycle, and production and secretion is inhibited by melatonin.8 Like several biological processes, melatonin can only illicit a response when it binds to its appropriate receptor, and the effect of melatonin on reproduction is said to be due to the stimulation of melatonin receptors.4 While the effect of lighting and its relationship to melatonin in the pig isn’t exactly well known, previous research showed one of the genes for the melatonin receptor is located on the same chromosome which also controls ovulation rate and litter size.9

Lighting regimens may have different outcomes for the sow and her productivity, and research is continuing to evolve with changes in nutrition, genetics, and barn environments. While the minimum light can be 100-150 lx in the breeding area3, previous research indicated increasing light intensity (range of 32 to 266 lx) and photoperiod for newly weaned sows tended to increase synchrony in returning to estrus within five days.10 Additionally, there was a tendency for gilts exposed to bright lighting conditions (433 lx) to have a slightly longer duration of estrus than gilts in darker lighting conditions (11 lx).11 Most farms in the post-weaning phase provide an intensity of around 300 lx, and a photoperiod of 16 hours of light and 8 of darkness controlled by a timer (Figure 3). According to a study completed in 2009, there is an improvement of 0.4 to 1.1 piglets with a 10 hour photoperiod for sows in gestation.12 This suggests a regulated photoperiod can be an effective environmental manipulation in improving sow reproductive performance.12

Light Impact in the Farrowing Room

There is some indication a lighting regimen can not only impact swine reproduction but can also affect both sows and piglets in the farrowing room. Changing the light regimen for sows can affect gestation length, and it was shown sows housed in dark environments gave birth approximately one day earlier than the expected herd average.13 Regarding the same study, the number of stillborn piglets was significantly higher in sows kept in a dark environment compared to those housed under prolonged light (Table 1); which may indicate available photoperiod can influence the events during parturition.13

| LIGHT TREATMENT | DARK TREATMENT | P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GESTATION LENGTH, DAYS | 117.2 | 116.4 | 0.026 |

| DURATION OF FARROWING, MIN. | 301.09 | 247.6 | 0.393 |

| INTERVAL BETWEEN PIGLETS, MIN. | 27.3 | 34.4 | 0.609 |

| STILLBORN, NUMBER | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.018 |

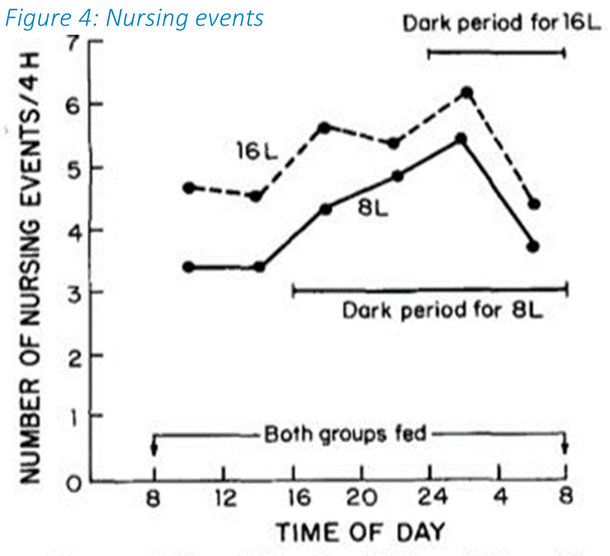

Aside from manipulating the farrowing process, lighting can also interact with lactation. Piglets exposed to a greater photoperiod may promote suckling.3 One study showed when using a 16L:8D regime, piglets are said to have more nursing events as opposed to eight hours of light as shown in Figure 4.14 Using this same photoperiod schedule, there was a 20% increase in total milk yield, total milk solids were increased significantly, and there was heavier piglet wean weights at 21 days of age.14,15 This result may have been due to encouragement of suckling.14,15 Another study with supplemental light for 16 hours a day also found increased piglet wean weights at 26 days old.10 As well, there was a greater amount of activity and increased creed feed consumption with increased photoperiod.

Regarding the immune response there have been some contradictory results, and the pre- and post-farrowing responses can be affected by manipulating photoperiod. One study has shown exposing sows to a short day, or 8L:16D, from day 90 of gestation to farrowing resulted in piglets potentially being more vulnerable to antigens at seven days of age.17 Over-exposing sows to 23 hours of light from day 112 of gestation to four days post-farrowing, then reducing the photoperiod for sows and piglets until weaning at day 23 reduced the piglets’ ability to develop a strong immune response.18

Wean to Finish

After weaning, early and consistent feed intake is crucial to avoid reductions in growth performance in the nursery phase. It has been demonstrated most weaner pigs did not start eating during dark periods of the day.19 No significant effects on any performance parameters during the first critical week were found with extended photoperiods.19 One study found that compared to 8L:16D regime, a 20L:4D photoperiod had no significant effect on performance metrics in the four days immediately post-weaning or any effect on performance during the entire nursery period.20 Additionally, feed disappearance in the first four hours and on the first day post-weaning tends to be greater in pigs housed in a prolonged photoperiod.20

Like the lactation period, there have been some instances of photoperiod found on the immune system during the wean to finish phase. Better immune responses have been found in weaned pigs given longer lengths of days (up to 18 hours of light).21 There are also improvements in health and weight of piglets treated to 16 hours of light compared to piglets exposed to only eight hours at 10 weeks of age.17

In the finishing phase, there is less information available, but it is suggested pigs perform better in terms of feed conversion rate (FCR) and average daily gain (ADG) under longer photoperiods.22 Within this same study, finishing pigs were exposed to either 14L:10D or 16L:8D and compared to the minimum of 8L:16D.22 Additionally, when increasing light intensity from 40 lx to 80 lx, there was no significant effect on either performance or slaughter characteristics in pigs.23 However, there is an improvement in behavior and a reduction in negative interactions between the pigs.23 The results of these studies suggest photoperiod has a greater influence on welfare and performance than light intensity.

Summary

In general, adequate lighting is important in maintaining proper environmental conditions in the barn. This is important for workers to be able to do their tasks effectively and safely. There is also some evidence to suggest it can impact animal productivity. Regarding literature, it is inconsistent on the impact of light intensity on several parameters. However, there is evidence that the availability of a correct amount of photoperiod is needed to maintain and optimize production. Overall, providing correct and sufficient lighting is essential in animal production and energy efficiency.

References

- AHDB. 2022. Lighting in pig buildings: The principles. https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge- library/lighting-in-pig-buildings-the-principles. Accessed 25 May 2024.

- HATO Agricultural Lighting. 2023. Lighting as an influencer of pig welfare and production. https://www.hato.lighting/en/hato-insights/knowledge-articles/lighting-as-an-influencer-of-pig-welfare-and-production. Accessed 01 August 2024.

- OMAFRA. 2022. Efficient lighting for swine facilities. #22-047. https://files.ontario.ca/omafra-efficient-lighting-swine-facilities-22-048-en-2022-11-18.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2024.

- Peltoniemi, O. A. T., and J. V. Virolainen. 2006. Seasonality of reproduction in gilts and sows. Soc. Reprod. Fertil. 62:205-218.

- Love, R. J., G. Evans, and C. Klupiec. 1993. Seasonal effects on fertility in gilts and sows. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 48:191-206. PMID: 8145204.

- Senger, P. L. 2012. Reproductive cyclicity - terminology and basic concepts. In Pathways to Pregnancy and Parturition. 3: 148-149. Current Conceptions, Inc.

- Olcese, J. M. 2020. Melatonin and female reproduction: an expanding universe. Front. Endocrinol. 11:85. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00085.

- Gelen, V., E. Şengül, and A. Kükürt. 2022. An overview of effects on reproductive physiology of melatonin. In Melatonin - Recent Updates. IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.108101.

- Ramírez, O., A. Tomàs, C. Barragan, J. L. Noguera, M. Amills, and L. Varona. 2009. Pig melatonin receptor 1a (MTNR1A) genotype is associated with seasonal variation of sow litter size. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 115:317-322.

- Stevenson, J. S., D. S. Pollmann, D. L. Davis, and J. P. Murphy. 1983. Influence of supplemental light on sow performance during and after lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 56(6):1282-6. doi: 10.2527/jas1983.5661282x. PMID: 6874610.

- Canaday, D. C., J. L. Salak-Johnson, A. M. Visconti, X. Wang, K. Bhalerao, and R. V. Knox. 2013. Effect of variability in lighting and temperature environments for mature gilts housed in gestation crates on measures of reproduction and animal well-being. J. Anim. Sci. 91(3):1225- 1236. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5733.

- Chokoe, T. C., and F. K. Siebrites. 2009. Effects of season and regulated photoperiod on the reproductive performance of sows. S. Afri. J. Anim. Sci. 39(1):45-54.

- McLoda, S., N. C. Anderson, J. Earing, and D. Lugar. 2021. Effect of light regiment on farrowing performance and behavior in sows. Animals. 11(10):2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102858.

- Mabry, J. W., M. T. Coffey, and R. W. Seerley. 1983. A comparison of an 8- versus 16-hour photoperiod during lactation on suckling frequency of the baby pig and maternal performance of sow. J. Anim. Sci. 57(2):292-295. doi:10.2527/jas.1983.572292.

- Mabry, J. W., F. L. Cunningham, R. R. Kraeling, and G. B. Rampacek. 1982. The effect of artificially extended photoperiod during lactation performance of the sow. J. Anim. Sci. 54(5):918-921. doi.org/10.2527/jas1982.545918x.

- Simitziz, P. E., V. Demitrios, N. Demiris, M. A. Charismiadou, A. Ayoutanti, and S. G. Deligeorgis. 2013. The effects of the light regimen imposed during lactation on the performance and behaviour of sows and their litters. Appli. Anim. Beh. Sci. 144(3-4):116-120. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2013.01.014.

- Niekamp, S. R., M. A. Sutherland, G. E. Dahl, and J. L. Salak-Johnson. 2006. Photoperiod influences the immune status of multiparous pregnant sows and their piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 84(8):2072-2082. doi:10.2527/jas.2005-597.

- Lessard, M., F. Beaudoin, M. Ménard, M. P. Lachance, J. P. Laforest, and C. Farmer. 2012. Impact of a long photoperiod during lactation on immune status of piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 90(10):3468-3476. doi:10.2527/jas.2012-5191.

- Bruinix, E. M. A. M, M. W. Heetkamp, A. Bohhart, C.M.C vad der Peet-Schwering, A. C. Beynen, H. Everts, L. A. den Hartog, and J. F. W. Schrama. 2002. A prolonged photoperiod improves feed intake and energy metabolism of weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 80(7):1736-1745.

- Reiners, K., E. F. Hessel, S. Sieling, and H. F. A. Van Den Weghe. 2010. Influence of photoperiod on the behavior and performance of newly weaned pigs with a focus on time spent at the feeder, feed disappearance, and growth. J. Swine Health Prod. 18(5):230-238.

- Yurkov, V. 1985. Effect of light on pigs. Svinovodstvo. 5:29-30.

- Martelli, G., M. Scalabrin, R. Scipioni, and L. Sardi. 2005. Effects of the duration of the artificial photoperiod on the growth parameters and behaviour of heavy pigs. Vet Res. Commun. 29(2):367-369. doi:10.1007/s11259-005-0367-8.

- Martelli, G., R. Boccuzzi, M. Grandi, G. Mazzone, G. Giuliano, and L. Sardi. 2010. The effects of two different light intensities on the production and behavioural traits of Italian heavy pigs. Berliner und Münchener tierärztliche Wochenschrift. 123(11-12):457-62. doi:10.2376/0005-9366-123-457.